10 Proteases for the Price of One

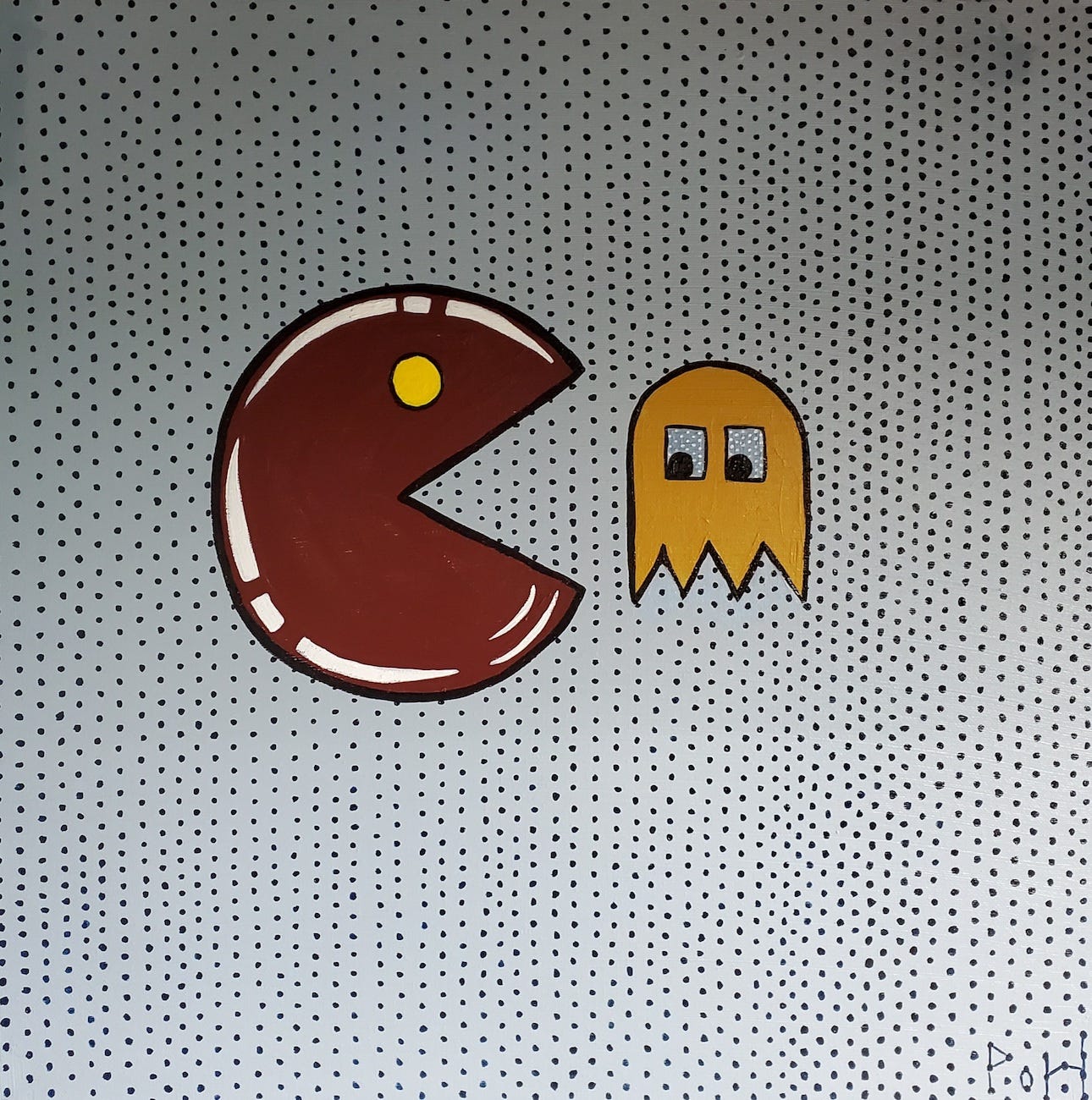

Here they are! The unseeable without the aid of an electron microscope. Proteases! Many in the shape and style of a Pacman hungering for a Blinky ghost. I was charged with the task of painting these microscopic wonders for a chemistry lab at a Canadian university. Its founder, Dr. T, is an art lover and was looking for something different in a logo. He used the Pacman before because it’s symbol expresses protease function to laymen the world over. (This helps when the lab needs to secure grants from pharmaceutical board members who understand the science of money, but not biology.) Dr. T found me and got what he was looking for. Me too. The most lucrative week’s work I have ever had. I sent the images to him back in July with an apology that none of them are what can be created by a graphic designer:

Dear Dr. T, I am not a graphic designer. It is no easy task pretending to be one for a logo project. Painters like me are messy and not very knowledgeable on how to “catch the eye”. Likewise, I could not scratch out from my mind the Pacman symbol, though I did manage a coven of macrophages and a constructivist rip-off. If none of these suit you, then please understand that I get it. You’ll have time to find a competent designer to make the reveal deadline. Either way, if interested, I could send the lot to you to give away to interested students, faculty, and friends. “Get an A in my class, and receive an original Ron Throop Protease”.

He wrote back:

OH WOWWWW. I LOVEEE THEMMMM! This is 100% perfect and awesome. I will let my team pick and rank their favorites. I already picked a top 3.

These days I have a much stronger respect for digital designers. After his approval, I varnished the paintings and packed them up securely in cardboard bound for Canada.

The first 5 paintings (title painting is #1) 18 x 18" acrylic on canvas, Proteases 1 - 5.

This one made it on the cover of an international biochemistry journal:

The last 5 paintings: 12 x 12" acrylic on canvas, Proteases 6 - 10:

Later that month I got the microbe painting bug:

Support Your Local Bacterium 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 16 x 13"

A Coven of Conspiratorial Viruses 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 17 x 13"

Finally, some dramatic words about my talents backdropped with a scary virus that once plagued these hills and valleys. From A Spring Without Mulch:

Finally, it’s Christmastime! I have been waiting with bated breath, else I get the coronavirus and die before welcoming the most wonderful time of the year. There is still a chance Rose and I could succumb before Christmas Eve—we’re breaking our quarantine this afternoon and will sneak into a big building to sing songs and make merry with a friend. This will be our first indoor visit with any person since March 13, 2020. I have done some grocery shopping over the summer and early autumn, and we’ve made a few visits to the drug and liquor stores. But not one social experience indoors since last winter. I agreed to this risk because we needed it real bad (some ice cold water splashed on our COVID fatigue), and Christmas is the season to express openly a renewed brotherhood and sisterhood. The internal suffering of guilt and sorrow is reserved for all the other Christian seasons. Which is why Christmas is special, even for non Christians like myself, the pretend atheist. I say “pretend” because only Jesus can call me a liar when I call out my diarrhea cramps in his name. And I’m not alone. I know some atheists who expect presents under the tree on Christmas morning. Many non-believers are good people and excellent pacifists like Jesus Christ, even if they are hypocrites and hangers on to other people’s faith in the absurd.

Anyway, I promised readers of my newsletter to secretly record a couple carols and post them as my holiday concert. My friend would be mad, but heck, we’re risking our lives for this low-key celebration. He’s the vector. The weak link. Not us. We plan to physically distance 7 paces with the windows open. Rose and I will bring bourbon and hand wipes. He’ll set up a charcuterie and pass out mugs of potent brown beer. We’ll be carefree and merry drunk an hour into practice.

When I was a young man in college I became obsessed by the star-making potential of the written word. An elective in early American Literature shorted some neuron switch in my college brain. I abandoned Business Administration for a degree in History after discovering how even bad writing of the Puritans could last the ages if written in a land of illiteracy. The Wampanoag didn’t need words to survive. They needed less Puritans who used their letters like a Protestant Dick and Jane primer on how to fear an angry God as occupiers of other people’s lands. The natives made oral sport of living. The Puritans literally chewed their fingernails off with the sin of being alive. They wrote nothing of artistic value. Page after page of catechism and historical record to last through the ages. Future History and English professors to pick apart the ONLY writing available in America pre-1680. In class we discussed William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation. I could barely get through the assigned passages of glory be to god, and “we are nothing but His faithful servants”, until I realized the potential which unknown writers could gain in an intellectual or creative vacuum. Even a stuffed-shirt, racist, religious fanatic like William Bradford could be disproportionately over-represented in a late 20th century college textbook. All he had to do was publish in a harsh land and keep it protected from the elements unto the next generation.

Voila! Future fame.

If William Bradford could make it into a survey of literature, albeit posthumously, then my chances were pretty good. I lived in an intellectual vacuum too. A sorority tabling in the college union had a banner hanging that read “Nuke Panama!”. On Sunday mornings students recited partially digested pizza and beer prayers to the porcelain God. There was drinking without thinking and enough idleness for the Devil to reach full employment at a Boeing Everett factory. I could become a writer. No one else I knew was taking up the art.

The Puritan fathers wrote for posterity a literature of religion. A Puritan woman, like Anne Bradstreet, could write poetry if themes were about mothering future obedient fathers of the colony. However if she tried publishing a book touting medicinal herbs, the brothers and fathers would burn and re-burn her at the phallic stake. To get my shot at celebrity, I would write 20th century narcissistic confessions like Time Magazine beatnik Jack Kerouac, or the tripping beach bum balderdash of Jim Morrison. I could achieve with words what I knew I would never get with the harder work of rock and roll. My hair was all wrong. I feared girls. I couldn’t play notes on the guitar because practice was for losers. I figured writing, even bad writing (a lá Bradford), would provide some lasting success. If I didn’t make the grade in my lifetime, at least history proved that, in American letters, death has its advantages for the mediocre.

At the time, my roommate’s Uncle had passed away and left a daily record of bowel movements covering the last twenty years of his life. Even that crap was saved to the next round of word worshipers.

I felt I could do better.

So I took up the college hobby of wordsmithing, and was capable as one would expect any unskilled apprentice to be. I got to familiarize myself with the tools of writing. Attractive journals, sleek pens, deadly sharp pencils, and a state of the art word processing typewriter purchased for under $200 at the Ames Department Store. I was going to be self-taught, forming and sticking with a blueprint of action to last a lifetime—not just in writing, but for all my endeavors in parenting, cooking, image-making, etc.

Enter the Ghost of Christmas Past to guide me back to a more happy and humble time…

I began by mirroring beat poetry mixed in with young Bob Dylan nonsense prose. It was easy doing. No expectations. Just string words around some “cool” subject matter such as hitch-hiking and social drug use. Sneak in allusions to titles of books or inspired passages by third rate authors known more for their romantic lifestyles than the literary ability to communicate. Allen Ginsburg published books. So could I.

For Christmas 1987, I printed my first volume of poems, My Brain is a Can of Worms on Speed, handmade from folded and stapled typewriter paper. I arranged five copies under the Christmas tree as presents to my parents, two best friends and girlfriend. It was a shining moment of success that filled me with immense pride. Something completely new and original, poured out of my heart and mind onto paper. What joy!

By New Years Day I received my first lesson in the power of social scorn/and or indifference. It was like I gifted my loved ones an accounting book of my bowel movements, and asked for critique.

One might sense correctly that, today, Ron Throop cannot hold a candle to a William Bradford, Jim Morrison or Allen Ginsberg. He is merely a living provincial artist of no consequence. However, tomorrow… Well, that depends on the course which human history will take. What I paint or publish in this lifetime could very well be of some value to future chroniclers of the 21st century, especially if those chroniclers are out seeking a representation of wisdom art and literature that suffered alongside banalities of celebrity. Substance might matter once again to a human world caught up in the bummer of reality. In trying times, young people seek those dead authors who in life objected to the pressures of safety careerism and sought alternative pathways to contentment. In addition, like an untalented William Bradford, they knew enough to document. I still feel as original as I felt that Christmas when I came out of the art closet. The only difference is that, what was original to me then, was just the act of “coming out”—no different from any artist’s first realization. Today I know I am original in the manner all artists yearn to be, because I have yet to discover another person who paints or writes from the same place I do. History will preserve me, even if allocated to some dry historical attic box where great grandchildren hide the family anomaly.